Intro

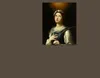

To make visible that which is invisible and scale divine heights: Guido Reni (1575–1642) set his sights high. Daring, cunning, and visually arresting, his paintings present glimpses of the extraordinary: sumptuous colours, beautiful bodies and compositions, but also scenes full of contrast and emotion. Long since forgotten and largely overlooked, the “divine” painter from Bologna was once a star among artists in his lifetime.